Shh…don’t tell anyone I’m a librarian. Just kidding, kind of…

A lot has changed since I first left my short career as a school librarian to enter into a library and information science master’s program.

When I was shopping for master’s programs, all advice and research pointed to applying only to programs for a MLIS, not a MLS. Employers wanted to see “Information Science” in your degree. Now many top schools are rebranding themselves as information science schools. Just this summer, the University of Illinois’s graduate school changed their name from the Graduate School of Library and Information Sciences to the School of Information Sciences and began offering new master’s programs in bioinformatics and information management in addition to their traditional LIS degree.

Two years ago, when I gave an interview for my school program’s alumni magazine, the editor changed my use of the word “librarians” with “information professional.” I was a bit weirded out by that at the time. I saw myself as a librarian interviewing in a library magazine.

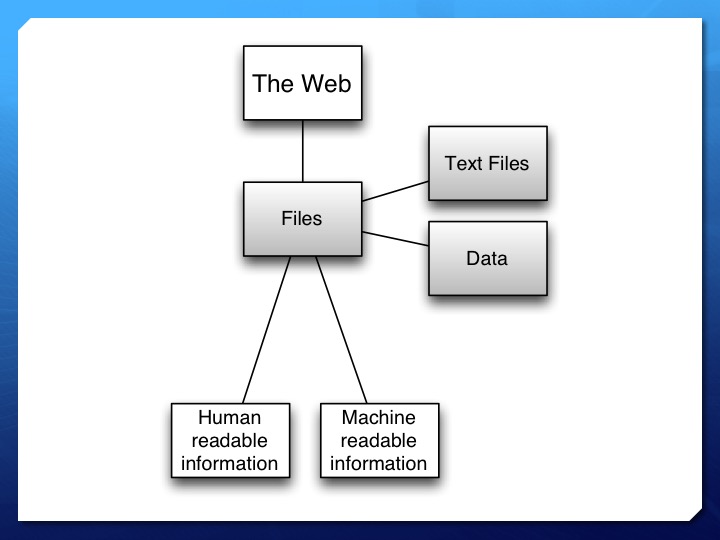

Over time, I’ve come around to accept, understand, and mostly approve of the term and label changes within my profession. There are many new directions the field has taken: scientific research data management, electronic document publishing, institutional repository development and management, and the list goes on. Our job ads are starting to have a lot in common with computer and software engineering postings.

The language we use to describe our profession must be robust enough to cover new specializations in addition to the core competencies for which librarianship is known.

So what’s with my personal hesitation of the l-label these days? I’ve found that you will most often be compared by people to the last librarian they met, such as their kid’s elementary school librarian. Don’t get me wrong, I know from personal experience that these folks are bright and talented, but if you aren’t an elementary school librarian, you really don’t want perceptions of your abilities narrowed to things you don’t do.

Even within your specialty, you’ll find people with greatly varying abilities. In many of my graduate classes, I had to take a survey over my skills, often coding or other technical knowledge, in order for the professor to select groups of students that could, together, complete assignments because alone many students lacked the background necessary to succeed.

It isn’t all bad, but you do need to compensate for inaccurate impressions. Learn to clearly and concisely explain what you specialize in. Make a portfolio demonstrating your work. I have two: a schoolwork portfolio available online and a more specific one with work samples (with the proper employer permissions, of course) that I make available in interviews.

For all of this, I will still accept the librarian title with pride, if only for one reason: the difference I see between librarians and all other information science professionals. Librarians’ primary goal is to add value to the community they serve in whatever capacity they serve. This could be through information resources, technology, or education. Sometimes things get political with librarians advocating for issues like equality, the digital divide, and poverty. This is a worthy group to be in.