artificial intelligence will become a major human rights issue in the twenty-first century

-Safiya Umoja Noble

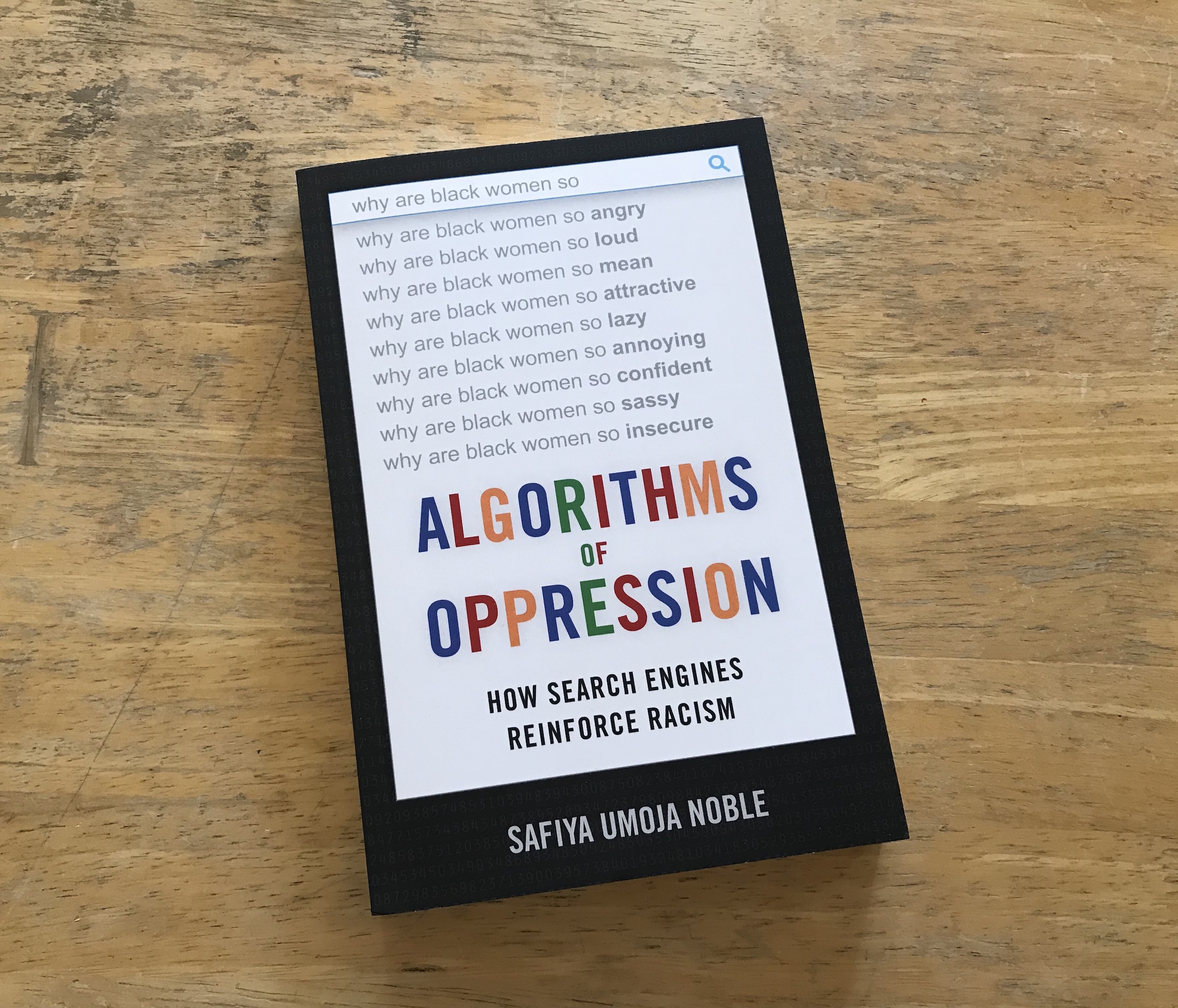

Big data algorithms can do some amazing things for society. They help us find information online, display advertisements for merchandise we might buy, recommend news articles we would be interested in, and provide new insights for research and development. They act as a mirror to reflect not only what we want but what we need. Unfortunately, this mirror also displays, even amplifies, our ugliest aspects. Author Safiya Umoja Noble focuses in on this problem with Google and its effects on black women in her latest book, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism.

Noble is a faculty member of the University of Southern California Annenberg School of Communication. She earned a Phd. and M.S in Library and Information Science from my alma mater, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It was through the U of I’s social media communications that I first learned about this book. The idea that there are serious flaws in the tech products we use in our personal and professional lives isn’t new. I bought the book because I was curious about what solutions Noble would present, but was blown away by a few problems I hadn’t previously considered.

As Noble points out, when algorithms support racism, it is extra problematic because people view the results as neutral, unbiased, and honest because it is coming from a machine. “Machines don’t lie. People do.” But machines are created by people for a purpose. With the near constant stream of sexual harassment and discrimination allegations and right-wing rhetoric from the tech industry hitting the news, the underlying motivations of many tech developers leak to the surface.

Noble acknowledges that many of her examples will be dated by the publication of her book, therefore, she attempts to present a pattern of misdeeds. One pattern she successfully lays out is how Google turns black women into sex objects, commodities, and stereotypes. This issue was first brought to Noble’s attention when she noticed that a search for “black girls” pulled up pornography sites on the first page of the search results.

Noble views companies like Google as information monopolies that are a threat to our democracy. As with other monopolies, they need to be regulated and busted up by the government. In addition to public policies changes, work needs to continue to close the digital divide affecting minority communities. The internet can be a great equalizer, but its opportunities are lost to those who don’t have easy access to it or the educational background to put it to use. Finally, Noble calls for more interdisciplinary research funding for these subjects.

I don’t disagree with Noble’s assessment of what needs to happen in the future, but I am pessimistic. Her solutions rely heavily on government funding and policy. Between rapid advancements and general misconceptions, lawmakers around the globe struggle to keep up with technology. Only recently have laws been put on the books in the U.S. making revenge porn a crime and in Europe giving people the right to be forgotten by search engines. This year the U.S. government repealed net neutrality, displaying a strong preference for big business over public interest.

I would like to see the contents of Noble’s book repackaged from this very academic work into something more consumable for the general public. Public outcry and embarrassments work. Google quickly modifies their algorithms when they receive bad press. Lawmakers change their focus when their constituents speak up. This type of grassroots movement can only happen if we, the content consumers, understand the issues and are able to spot them for ourselves.

Noble opened her book with the assertion that “artificial intelligence will become a major human rights issue in the twenty-first century.” Maybe we need to listen to the lessons our parents and grandparents learned in the last century. Doing nothing isn’t an option. Racism in whatever form it presents itself in won’t resolve naturally with time. To push for change, we must educate ourselves, listen to and believe our neighbors, point out the injustices we see, and vote.